Originally created as Armistice Day after World War I, it was renamed “Veteran’s Day” after World War II. To commemorate Veteran’s Day in 2014, we will be sharing excerpts from our book Staying Alive: How to Act Fast and Survive Deadly Encounters. This is Part 3 of 3 of our Veteran’s Day series. For our final installment in this series, we feature the story of co-author Stephen Satterly’s brother, Tom Satterly. Tom served as a special operator for many years and saw action in Somalia as featured in this story. Tom also was part of the team that helped capture Saddam Hussein (more on this in the video after the excerpt). Tom Satterly is a “real American hero” in the flesh and has some truly amazing stories. For more on surviving traumatic stress, buy Staying Alive: How to Act Fast and Survive Deadly Encounters on Amazon.

From Staying Alive: How to Act Fast and Survive Deadly Encounters, Chapter 13: “Hope, Confidence and Resilience as Tools for Survival: You Can Do This!”

How to Improve Your Crisis Resilience

Nobody wants to fail in a crisis, but some of us prepare to do so inadvertently. There are those of us who take steps to prepare, and then there are those who fail to prepare, and thus are preparing to fail. Abe’s preparation by taking training in martial arts saved his life and the lives of four others. Marcus Luttrell’s training saved his life in Afghanistan. How can you take advantage of these same techniques without knowing what threat you might face?

We have introduced you to numerous skills like threat assessment, ways to build situational awareness, pattern matching and recognition to detect danger, and mental simulation to allow for stress inoculation. None of these skills will help you at all if you do not train yourself to use them, and use them well. One of the goals of training is to develop muscle memory. When a crisis occurs and your heart rate rises, you lose cognitive function and some manual dexterity. If you have developed muscle memory, your body will perform without thinking.

Reloading a gun in the middle of a shootout is a prime example of a skill that needs to be trained into muscle memory. Though a relatively simple action with a semiautomatic pistol, it can still be extremely challenging to reload while being shot at. The simple steps of pressing a button to drop an empty magazine, grabbing a loaded magazine, properly orienting it to the gun, pushing it into the magazine well, slapping it on the bottom to make sure it is seated properly, releasing the slide of the weapon to chamber the first round of ammunition, and firing the weapon takes considerable practice. To be able to perform these steps in a gunfight at 3:00 A.M. requires even more extensive hands-on experience. Practicing and training can dramatically help improve your ability to respond to crisis situations and save lives.

One man who can attest to this is Tom Satterly. Tom recently retired from the U.S. Army after serving twenty-five years, most of them in Special Operations. His first four years were spent as a combat engineer in the 54th Engineer Battalion in Wildflecken Germany. When Tom reenlisted, he went through Special Forces Qualifications, passed, and joined the 5th Special Forces Group, stationed in Ft. Campbell, Kentucky. The life of an elite Green Beret did not satisfy him, so he applied for even more elite schools, specifically the Selection Course for the Operator Training Course (OTC) – the training for what we know as the “Delta Force”.

Tom Satterly early on in his military career.

In 1991 he made it through Selections and the grueling OTC to become a Delta Operator just as the First Gulf War was ending. His first service as an Operator was in Mogadishu, Somalia, where he spent a hellish night of combat in the action that become immortalized in the movie Blackhawk Down. For his valorous service in that operation, he was awarded a Bronze Star with a special commendation for valor. During the rest of his military service as an operator, he was involved in missions in Bosnia, Kuwait, Columbia, and Iraq, where he was the leader of the second Troop on the scene when Saddam Hussein was captured.

At this time Special Operations Command (SOCOM) decided to form a new squadron. Tom became one of the first members of this new Squadron, which was meant to keep Operators constantly deployed rather than having voids of inactivity. He also served in Algeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, where he saw combat numerous times. At the end of his service, he had earned five more Bronze Stars, two with special commendations for valor, and now suffers quietly with his pain from his injuries and the loss of friends in combat.

When Tom was asked how he stayed alive through all these harrowing missions, he simply replied, “Training. Always train.” (T. Satterly, personal communication, July 12, 2013). Irwin Rommel, the famous ‘Desert Fox’ from World War II, would agree. He is quoted as saying, “The more you sweat in training; the less you bleed in battle” (Grossman, 2011). Proper training has a two-fold purpose: to teach the trainee a practical skill and to inoculate the trainee from the stresses they will feel while using that skill under duress.

Like public safety officials, you should decide what you need to practice, how you will simulate it, and then practice that way, over and over and over. For example, a police officer could improve their own training by adding stress to their shooting drills by trying to reload while being timed and having someone fire a pistol nearby to simulate the sounds of a gunfight. They might also simulate the stress of combat by running a few sprints, and attempting to change their magazine while their heart rate is elevated. As with any type of drill, adequate safety precautions should be implemented, especially when firearms are involved, loaded or not.

One simple but important concept that you can use when you practice for an emergency is called tactical breathing, or controlled breathing. To use controlled breathing, take in a full breath through your nose while silently counting to four, letting your belly expand, then hold for a count of four before exhaling through your mouth for a count of four, letting your belly deflate. This process should be repeated as many times as necessary as appropriate to slow your heart rate enough to be able to perform the task at hand (Grossman, 2011).

The key is to practice each action and slowly add additional skills, committing each to muscle memory. As you practice, take this time to engage in mental simulation. Envision yourself in a situation where you need that skill you are practicing. Visualize yourself being successful. Tom Satterly’s advice is, “Never visualize yourself losing.” (T. Satterly, personal communication, July 12, 2013). This means that even if you make a mistake, you should visualize yourself correcting it and successfully completing the scenario. If you wonder if this type of training really works, you could ask Captain Zan Hornbuckle, an Army officer during the invasion phase of the war in Iraq. At one point, 300 Iraqi and Syrian fighters surrounded him and his eighty men. Captain Hornbuckle and his unit engaged the enemy for eight hours. In the end, 200 of the enemy were dead, with zero American casualties (Grossman, 2011). This success is even more amazing considering that none of Hornbuckle’s soldiers had ever been in combat before.

While we have used examples from military combat to help convince you of the power of these concepts, you should consider how practicing these simple yet important skills and habits can save your life in everyday situations. For example, you should mentally prepare yourself and practice the important habit of leaving behind your belongings before moving to safety in a crisis. While you may need to take your cell phone or radio before retreating to safety so you can call for help, you should not fall prey to the common tendency for people to take precious time to gather personal items before moving to safety. There are a number of real life examples of this gathering behavior, including many occupants of the World Trade Center towers who took the time to gather purses, books, and other mundane personal items before evacuating. (Ripley, 2008).

Believing in Yourself

The physical skills needed to survive are absolutely important, but they would be improved tremendously with the belief that you can do what needs to be done. Captain Hornbuckle spent considerable time reminding his men that they could do extraordinary things in battles. He also emphasized that they needed to remember their training. Once the bullets started to fly, one of his primary jobs was to keep his men calm so they could remember their training. Tom Satterly recounts of his combat experiences, “If you have to think about what you are going to do, you’re lost. I developed confidence in myself because of the training. Don’t train to lose. You’re never calm, but you are methodical,” (T. Satterly, personal communication, July 12, 2013).

There will be times when you get frustrated, mad, and even upset. You may feel sore or get blisters, and wonder if the training is worth it. This is natural. But in a life or death situation, you cannot quit. As one SEAL instructor told Luttrell during Basic Underwater Demolition (BUDs) training, “The way out of that is mental – in your mind. Don’t buckle under to the hurt; rev up your spirit and your motivation,” (Luttrell, 2007). Tom Satterly echoes that sentiment, “Don’t give up in your mind. If you do, your body will follow.”

One of the main points of SEAL training, Operator training, or Ranger training is to instill in the men who go through that training the belief that they can do whatever has to be done. During the American conflict in Vietnam, two Ranger School graduates found themselves under fire in a rice paddy. Facing a heavy onslaught from the enemy, one looked at the other and said, “Well, hell, at least we’re not in Ranger school.” (Grossman, 2011). You do not need to go through their level of brutal training to feel that same confidence within yourself. Basic personal preparation can help you develop the confidence you need to survive deadly encounters.

But belief in yourself is sometimes not enough. In a crisis, you will rarely ever be responding by yourself, but with others. Even though our favorite movies and TV shows focus on main characters that are “lone wolves”, in reality, responding to an emergency is a collaborative effort. Thus, while it is important for you to believe in yourself, it is no less important to believe in others who can help you during a crisis.

When Tom Satterly was in Mogadishu, things were bleak. His unit was in a firefight for eighteen hours straight, and it seemed as if they were fighting the entire city. When asked how he got through it, he replied, “I remember thinking, ’Are we ever going to get out of here?’ The higher ups, not on the ground, kept covering us with the Little Birds (gunship helicopters), getting the armor together from the Pakistanis. We knew we hadn’t been forgotten. You knew the other guys were doing their stuff, so you kept doing what you had to.” His belief that others were doing their job was one of the main factors that kept him doing his job.

The Power of the Mind

In 2011, Dave Grossman was interviewed for The First Thirty Seconds DVD training and evaluation series. In it he is quoted as saying, “The greatest survival tool the world has ever seen is the properly prepared human brain.” (Dorn, 2012). We believe Grossman is correct in this regard. The power of visualization, confidence, and hope are all derived from the human mind.

As Klein points out, there is considerable evidence that our brain can help us make correct life and death decisions with amazing speed and accuracy (Klein, 1998). Tom Satterly and Marcus Luttrell are two prime examples of just how much a human being can do to survive against seemingly impossible odds. While very few people will ever face situations as dire as these men, their drive to survive at all costs affords us powerful lessons that we can all apply. It would be a shame not to learn from their amazing efforts.

Know that You Can Do This!

As you read earlier, stay in touch with yourself, remember your preparation, and visualize yourself successfully completing the task. Above all, maintain hope. Hope is the understanding that, as bad as things might be right now, they will be better. Hope is not a strategy; it is a mindset. Tom Satterly was mired in seemingly endless combat in Mogadishu but never lost hope because he had confidence in his own abilities as well as those on his team.

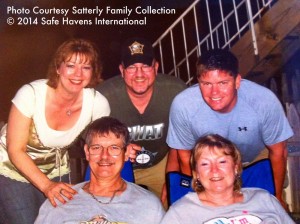

Co-author Steve Satterly (top row, middle) and his brother Tom Satterly (top row, right) with their family members.

Sources:

Michael Dorn. (2012). Safe Topics: The First 30 seconds. Safe Topics. Macon, GA: Safe Havens, International.

Dave Grossman; Loren W. Christensen. (2011). On Combat: The Psychology And Physiology of Deadly Conflict in War and Peace

Gary Klein. (1998). Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Mark Luttrell & Patrick Robinson. (2007). Lone Survivor: The Eyewitness Account of Operation Redwing and the Lost Heroes of SEAL Team 10: Little, Brown.

Amanda Ripley. (2008). The Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes – and Why. New York: Three Rivers Press.

View a portion of the interview where Tom Satterly discusses how you can use some of the same skills that he used in combat to survive everyday trauma:

Staying Alive – Combat and Lessons for Every Day Crisis Stress from Safe Havens International on Vimeo.

And hear about how Tom Satterly used Pattern Matching and Recognition to help capture Saddam Hussein:

Staying Alive – Pattern Matching & Recognition from Safe Havens International on Vimeo.